The Supreme Court’s decision this week inspired millions of people to declare their expertise on the U.S. Constitution and weigh in on the Court’s decision to uphold the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This blog isn’t about constitutional law and I see no point in adding another marginally informed voice to that debate. Maybe I don’t know enough about how the Supreme Court operates but it seems unlikely to me that Chief Justice Roberts will read this blog and decide to reconsider the case.

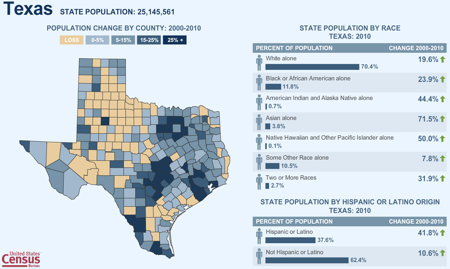

Instead, we should focus on the impact of the decision on Texas. State government needs to make a double of decisions pretty quickly.

The state will need to create a state health insurance marketplace where individual Texans and businesses can shop for health insurance. Texas and other states have until January 1, 2013 to demonstrate to the Department of Health and Human Services that their system will be up and running by January 1, 2014. If the state doesn’t create an exchange the federal government will create one.

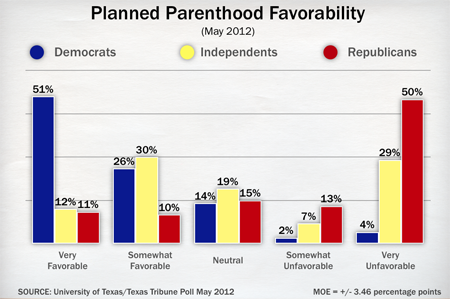

The state government will also be offered funds to extend Medicaid to more Texans. Under ACA, Medicaid would cover everyone with incomes under 133% of the federal poverty level (about $31,000 for a family of four). Initially, federal funds will pay for 100% of the expansion. However, that rate will drop to 90% by 2019. Many of the state’s leaders are vowing to turn down these federal dollars. The problem is that people under the federal poverty level will not be eligible for the subsidies the law provides to buy their own coverage. These people will lobby for coverage and the hospitals that have to take care of them will lobby the state to eliminate this gap in coverage to make sure they don’t get stuck with the costs.

The Texas Tribune has brought in a couple of guest columnists to highlight the promise and perils that Texas faces with the implementation of ACA. Arlene Wohlgemuth, the executive director of the Texas Public Policy Foundation, argues that the law places an undue burden on businesses and further strains an already overburdened Medicaid system. Anne Dunkelberg, the associate director of the Center for Public Policy Priorities, makes the case that the law is imperfect but a good start on providing coverage to the 6.2 million Texans don’t have health coverage. These two columns do a pretty good job of sketching out the debate and are a good starting point for a meaningful debate about what Texas should do next.

Filed under: Public Policy | Tagged: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 | Leave a comment »